IHGC Annual 2014-2015

You get pegged as an optimist, and then they smile when you talk. They pat you on the head, meaning to be affectionate, even while they patronize your vision and conviction. It’s annoying, but I accept the condescension gladly. It’s a small price to pay for the chance to carry on thinking, talking, and building a community in which so many of us deeply believe.

When I say ‘they,’ I mean those too impatient to consider what the humanities means and brings — certainly not our partners in aspiration, our colleagues in Delhi, Beijing, Stockholm, Dublin and elsewhere. Those of us who have joined together in the last fifteen months share the gleam of possibility. Now in late May we know afresh what the humanities can be, because we’ve just finished living through an example of what international cooperation can mean to the cause.

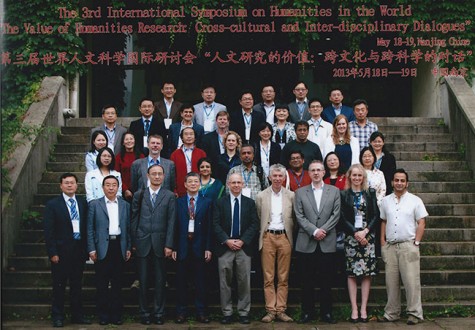

Our third international conference under the Global Humanities Initiative was held at the University of Nanjing, May 17-20. Five traveled from India, and five from Charlottesville, three from Britain, one each from Sweden and Ireland – all to join fifteen Chinese scholars in the event under the noble title: “The 3rd International Symposium on Humanities in the World – The Value of Humanities Research: Cross-Cultural and Inter-disciplinary dialogues.”

It was exhausting, because exhilarating. We had talks on Chinese opera and Indian refugees, on Confucius and Max Weber, on gardens and tents, happiness and empathy. And that was just before tea. The group photo hovering above is a visual sign of what’s happened in these fifteen months: the standing together, shyly but proudly, the sense of resolve and the sense of humor, the desire both to dwell among the rigor of ideas and then to carry thought into the imperfect world.

As of this morning (May 28, 2013) we have firm and growing partnerships with the new Oxford humanities center (T.O.R.C.H.), with Marg Humanities (the Humanities Way) at Delhi University, with the School of Oriental and African Studies in London, and with Nanjing University’s Institute for Advanced Studies in Humanities and Social Sciences.

The first of our international conferences was held in Charlottesville in April 2012, the second in Delhi in August of that year. In October, we meet in a smaller group here at U.Va. Our subject will be Cosmopolitanism, our keynote speaker Thomas Pogge of Yale, our guests from all over Latin America.

See more photos from the conference by visiting our facebook page.

Go to original in the Richmond Times-Dispatch

The humanities will not go quietly. They won’t disappear unless and until we agree to be machines instead of persons. As long as we still ask about a past before we were born, or the lives of others in distant places, or the meaning of actions and objects we don’t understand, or the values by which we choose to live, there will be the humanities. You can starve them, but you can’t kill them off.

It’s important to stay reasonable as we discuss the future of universities, but now is also the time to be angry. The crudeness of the debate is unworthy; it has become shallow and sordid. This idea that the humanities are self-involved and impractical, preening and primping, is a cartoon that does not tell the truth. Elitist? Then why are students of every background and aspiration intent to study Descartes, Rembrandt, DuBois? Impractical? The record is clear: Business leaders preach the virtue of flexible thought that sees the possible surrounding the actual, and the Chinese now require liberal arts for first-year students across their country, in an effort to break the grip of rote learning. Jargon-ridden? Sometimes. But any field – from sailing to baking – develops a language of its own, opaque to newcomers.

You can find narcissists under any rock, but anyone who spends time in earnest conversation with students these days – young philosophers, classicists, religious and literary historians – knows that they are engaged and transformed by the subjects they study. And that students admire their instructors. Ask yourself: Why do they refuse to sell out – the ill-paid, hardworking young scholar/teachers? Why are they stubborn in their sense of calling? Why do students still testify to the way lives can change in a seminar on the French Revolution, Etruscan art, the Irish literary revival, the ethics of Aristotle?

What has skewed the debate is the absence of the very virtues taught in the humanities: patience, thoroughness, close attention, multiple perspectives, honest self-questioning. Yes, the STEM subjects (science, technology, engineering, mathematics) are indispensable. As we invent and make new things for our material flourishing, we need training and skills for more students. But who can doubt that we also need to comprehend the significance of what we make? What’s it for? How does it belong to our higher purposes? How does it fit within the wide context that surrounds our narrow band of life?

In fact, STEM and the humanities (HUMS) are close siblings. There is making and thinking on both sides. We learn from one another, stir each other to new ideas – physicists and historians, anthropologists and classicists, engineers and artists. Within the university, scientists and humanists have mutual, abiding respect. We share the cause of free inquiry that must follow its path to understanding, wherever it leads.

No making without meaning seems indisputable. Does anyone really want to live as an amnesiac, with no history to remember or future to project? No one wants to be lost in space and time, unsure of before and after, unclear about near and far. Everyone wants to express their thoughts with conviction and lucidity. We all need to compare ourselves to others; we need contexts for our actions. This is what the humanities give. Our subjects are anything but luxuries: They are the conditions of human thriving.

Nowadays, we specialize in the hysteria of false urgency. Everything will be changed by tomorrow, people say. We won’t need lecturers, who appear in the morning, fueled by coffee and vision, trying not only to teach their subjects but also to show in voice, gesture and glinting eyes why the subject matters. Everything can be online, we’re told. We don’t need to gather, to share the rhythm of thought, just because people have done this since Socrates met them in the agora.

I love the screens: They too have glinting eyes. Connections across waters and continents have changed my life, my teaching. As they change more, I’ll be there. But let’s not be hysterical. We still look more or less like those who lived thousands of years ago; our brains aren’t much faster; we still soften to a blazing sunset and search for words to explain the mystery. Really, what could be more arrogant than to think that the Transformation-of-Everything would happen in our lifetime?

The world is changing, but – sorry, anti-humanists – it’s still recognizable. If you come to a classroom (instead of imagining one), you’ll find that present-generation students resemble students of the past far more than they differ from them. Twitter hasn’t created robots. Students want to sift meanings, recover the past, articulate values, discover a vocation and fall in love.

Humanities Week will be held at U.Va. from April 8 through 12.

Michael Levenson, William B. Christian Professor of English at the University of Virginia, is director of the Institute of the Humanities and Global Cultures and author most recently of “Modernism.” He can be reached at mhc@virginia.edu.

This past July, I embarked on a trip that began in the Hague at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), extended through Nuremberg and the now-historic Courtroom 600 where the Nazi war crimes trials took place, and ended in the Republika Srpska territories in the northeast Bosnian village of Potočari, where the Srebrenica Genocide Memorial now stands. Seventeen years earlier, more than 8,000 Muslim men and boys were killed by the Bosnian Serb Army in an area that had been deemed “safe” by the United Nations, and the city of Sarajevo had lain under uninterrupted siege for more than three years. The salient bullet and mortar wounds in the concrete facades along the Ferhadija and banks of the Miljacka contain traces of Sarajevo’s recent past, while the road that leads from Sarajevo to Srebrenica (from the Federation of BiH and into Republika Srpska) weaves through extraordinarily lush green hillsides consistently betrayed by the skeletal remains of homes and farmhouses destroyed during the war, and red skull-and-crossbones signs that warn their readers to watch out! in both the Bosnian Latin and the Serbian Cyrillic alphabets—pazi, пази—for the landmines that make those hills now impenetrable. Yet too, the edges of these peaks are dotted with colorfully painted wooden beehives, boxes producing thick and sweet Bosnian honey for baklava, tefahije, and other sweets that line the shop windows in Sarajevo’s baščaršija.

In the early 2000s, Aleksandar Hemon’s first book, The Question of Bruno, sparked my interest in literature from the former Yugoslavia, and it later shaped my legal focus on international human rights law. Thinking about literary descriptions of the city of Sarajevo and the experiences of war in Bosnia, I carried images from Hemon’s novels, as well as those from the earlier works of Danilo Kiš and Ivo Andrić, with me on this strange trip layered with history, literature, and law.

In the early 2000s, Aleksandar Hemon’s first book, The Question of Bruno, sparked my interest in literature from the former Yugoslavia, and it later shaped my legal focus on international human rights law. Thinking about literary descriptions of the city of Sarajevo and the experiences of war in Bosnia, I carried images from Hemon’s novels, as well as those from the earlier works of Danilo Kiš and Ivo Andrić, with me on this strange trip layered with history, literature, and law.

On May 26, 2011, Ratko Mladić, Colonel General of the Bosnian Serb Army, was arrested for crimes against humanity and genocide in Bosnia—specifically for his role in the killings in Srebrenica—for which he had been indicted more than ten years prior. Less than a week after his arrest, he was transferred to the ICTY in the Hague, where his trial commenced on May 16, 2012. Beginning in mid July, I observed this trial behind the plate-glass walls that separate the tribunal proceedings from the viewing public. The ICTY courtroom space stands in sharp contrast to its precursor in Nuremberg, which convened at the Palace of Justice from 1945-46 near the physically destroyed center of Bavaria.

At the ICTY, all observers arrive before the trial day begins and sit facing a dark-curtained wall, fumbling with earpieces that translate between English, French, German, and Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian (BCS). When the clock (digitally) strikes the trial’s commencement, the curtains electronically pull back, revealing the panel of judges, the attorneys, and the defendant, already seated with only a small number of feet between all of us. My eyes moved immediately toward the man I assumed to be Mladić, sitting in the back left of the courtroom, physically framed by uniformed U.N. guards. I had seen numerous photographs in newspapers and news stories from the 1990s, but I hadn’t seen an aging man in ornate glasses gripping a book, free from handcuffed confinement, with a small water pitcher and glass at his table. Occasionally, he smiled. I thought of Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem and her reports from his 1961 trial that emphasized the banality of evil. I had expected Mladić to look like a monster. I am still unsettled by his physical normalcy, even as I recall him yelling in stark and disquieting Serbian to his attorneys seated below.

Images from Mladić’s trial followed me to Sarajevo as I meandered through the streets in anticipation of my trip to Srebrenica. I spent time in the city’s historical archive, which contains objects from the siege, collected and saved by the residents of Sarajevo. The building itself bears few traces of postwar restoration, save for the replacement of broken windows and doors. Inside, the floors and ceilings are marked with discolored holes and larger mortar marks—indentations one is forced to step upon to move throughout the space. Around the rooms, small tables and cases are filled with makeshift cooking appliances, homemade weapons, improvised military uniforms with puma sneakers from the early 1990s (which I remembered from my American classmates’ feet during gym), newspaper clippings, photographs, and so many objects—large, small, and seemingly banal—left behind on the streets by victims killed during sniper fire. A small sign in the entryway refers to the space as a “living museum.”

As the only route to Srebrenica is by an unreliable bus running once per day, the owner of the Sarajevo guest house where I was staying would be doing the driving. On July 26, after a nearly four-hour journey through the winding roads carved out between Sarajevo and the northeastern banks of the Drina river, I arrived in Potočari, where uniformed Bosnian police officers and photojournalists had lined up along the paved walkways of the Srebrenica Genocide Memorial and its cemetery. The Muslim grave markers weave across this otherwise-desolate area, interrupted only by newly dug graves and number “markers,” set aside in piles, in wait for yet more victims to be uncovered and later buried here. The almost-anthropomorphic grave markers stand resolutely (or perhaps, I hope they do). For the first time since the genocide in 1995, a U.N. Secretary-General would be visiting this site, in conjunction with a trip throughout the regions making up the former Yugoslavia. Before Ban Ki-Moon’s helicopters touched down on the plot of land where U.N. soldiers had stood (also resolutely, I imagine), as the Bosnian Serb Army killed more than 8,000 people, I overheard a conversation among a few reporters and a man with keys to a bulldozer. I learned that more bodies had been found just outside the cemetery, and they were to be excavated upon Ban Ki-Moon’s departure. After Ban’s speech, which focused on the seemingly parroted phrase that “we must learn from the lessons of Srebrenica,” he boarded a U.N. helicopter, and I saw the bulldozer begin to break ground, so to speak, in the close distance.

As the only route to Srebrenica is by an unreliable bus running once per day, the owner of the Sarajevo guest house where I was staying would be doing the driving. On July 26, after a nearly four-hour journey through the winding roads carved out between Sarajevo and the northeastern banks of the Drina river, I arrived in Potočari, where uniformed Bosnian police officers and photojournalists had lined up along the paved walkways of the Srebrenica Genocide Memorial and its cemetery. The Muslim grave markers weave across this otherwise-desolate area, interrupted only by newly dug graves and number “markers,” set aside in piles, in wait for yet more victims to be uncovered and later buried here. The almost-anthropomorphic grave markers stand resolutely (or perhaps, I hope they do). For the first time since the genocide in 1995, a U.N. Secretary-General would be visiting this site, in conjunction with a trip throughout the regions making up the former Yugoslavia. Before Ban Ki-Moon’s helicopters touched down on the plot of land where U.N. soldiers had stood (also resolutely, I imagine), as the Bosnian Serb Army killed more than 8,000 people, I overheard a conversation among a few reporters and a man with keys to a bulldozer. I learned that more bodies had been found just outside the cemetery, and they were to be excavated upon Ban Ki-Moon’s departure. After Ban’s speech, which focused on the seemingly parroted phrase that “we must learn from the lessons of Srebrenica,” he boarded a U.N. helicopter, and I saw the bulldozer begin to break ground, so to speak, in the close distance.

Upon arriving back in Sarajevo, I spent time tracing some of Aleksandar Hemon’s steps from his New Yorker short story, “Mapping Home,” in which he describes his 1997 return to the city after years of living in Chicago. In the meantime, images from the Ban Ki-Moon visit to Srebrenica, unsurprisingly, showed up on a number of news media sites. My driver had seen himself in a Free Radio Europe clip, prominently walking among the graves. “My family says I’m famous,” he laughed.

[photo: Sarajevo. All photographs taken by the author, Audrey Golden.]

Last night, the Institute was proud to support the members of the undergraduate humanities initiative as they presented short readings on life, literature, and — like the title says — everything else: nostalgia, technology, giving, DFW, waiting, Beckett, the Little Mermaid, feminism, Coetzee… the list goes on. Enjoy!

Full description of the event:

Presented in cooperation with the Institute for the Humanities & Global Cultures and the Leadership Network, On Being Human is a night of 7 short lectures on what it means to be a human in the modern world.

Inspired by TED Talks and Look Hoos Talking, On Being Human is a forum for some of the University’s brightest undergraduates to talk about how they see the world & and their role within it. Each talk will be approximately 8 to 10 minutes in length. It is a night that promises to be thought-provoking, sincere, and a great way to clear your head before finals begin.

The speakers will be introduced by Professor Michael Levenson, Director of the Institute for the Humanities & Global Cultures, and William B. Christian Professor of English.

Our speakers are:

Hillary Hurd (at 08:35)

Aaron Eisen (at 11:50)

Zainab Al-Sayegh (at 22:05)

Emma DiNapoli (at 34:07)

Katy Hutto (at 39:55)

Charlie Tyson (at 50:12)

Eric McDaniel (at 1:03:02)

GLOBAL COMMUNITIES

THEORIZING THE GLOBAL

ONLINE LEARNING

On Monday, we welcomed Hunter Rawlings, the President of the Association of American Universities, to speak as a part of our series of discussions on the Future of the University. To a room filled to capacity, Rawlings gave an impassioned defense of the value of the public university.